William Ralph Blass

PFC in 603rd Engineer Camouflage Bn : Co B, 4th Platoon

Born 1922 in IN, Died 2002

Artist

Other residence(s): New York, NY; New Preston, CT

United States Army, European Theatre of Operations

College education before the war: McDowell School (NYC); Parsons

College education after the war: Parsons?

Bill Blass was born on June 22, 1922 in Fort Wayne, IN, the younger of two children. His mother was a part-time dressmaker; his father was a traveling salesman who committed suicide when Bill was only five years old.

He attended South Side High School in Fort Wayne, graduating in 1940. His yearbook says that he served as the decorating chairman for the sophomore and junior banquets—demonstrating an interest in style from an early age. "Something about glamour interested me," he told People magazine in 1999. "All my schoolbooks had drawings of women on terraces with a cocktail and a cigarette." He started his career designing prom dresses for girlfriends. Around the same time he began selling evening gown designs to a New York manufacturer for $25 each.

He was inspired by Marlene Dietrich and fellow Hoosier Carole Lombard and years later he said that "those women inspired me, and I had to get out." Before he left Fort Wayne, he was the winner of a cash prize in the 1940 Chicago Tribune's American Fashion Competition.

In the summer of 1940, he moved to New York to study fashion at the McDowell School of Fashion and later at Parsons School of Design. He also worked as a sketch artist for the David Crystal Company, a women's clothing manufacturer.

Bill registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, a week after his 20th birthday. In 1943, along with other New York City artists, he became a member of the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion. His fellow soldiers remembered his positive attitude and his sense of style. In The Ghost Army of World War II, Bill Sayles is quoted: "He would never shirk a duty. If it was cleaning trash cans, he was right there with a smile and beautiful teeth." And Jack Masey reports that Blass read Vogue in his foxhole.

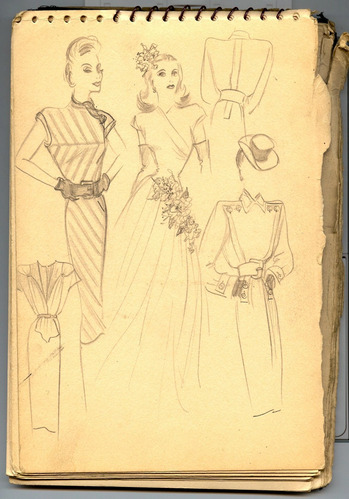

Image from one of Bill Blass' wartime notebooks, courtesy Bill Blass Group

In a 2013 article in the New York Times, journalist Cathy Horyn, the editor of his 2002 memoir, Bare Blass, wrote: "I think for Bill, who had grown up surrounded by women and had felt keenly the absence of male figures, the war years represented something quite personal, and at the heart of his character. As he said to me, handing back my first inept draft of the war chapter, 'Kid, I don't know if you can understand what this period meant to me. It's really a man's story.'"

After the war he returned to New York and joined Anne Klein as an assistant, though that job was short-lived. According to his obituary in the New York Times, Bill later recalled, gleefully, that "she said I had good manners but no talent."

He continued to produce his own designs. In 1948, he and fellow Ghost Army veteran George Nardiello were among the winners of the Chicago Tribune American Fashion Competition. Nardiello and Blass would go on to see their designs among the winners almost every year through 1953.

He eventually found a job at a manufacturer named Anna Miller. When Ms. Miller retired in 1959, her business was merged with that of her brother, Maurice Rentner. Bill's designs gradually became recognized, and he got his name on the label: "Bill Blass for Maurice Rentner." In 1970, he bought out the Rentner firm and changed the name to Bill Blass Ltd.

He was best known for his sportswear and also incorporated elements of sportswear into his high fashion lines. According to a 2020 article by Megan Smith, conservation lab manager at the Indiana State Museum (which holds a rich collection of Blass designs): "American couture meant casual elegance: knits worn with satin or shirting fabric at a gala. Bill was a master of this chic and luxurious vibe. His designs were worn by society's movers and shakers, and as a result, Bill became a fixture of New York's social scene in the 1970s and 80s."

He expanded his line to include swimwear, furs, luggage, perfume, and chocolate. He was the first American couture fashion designer to start a menswear line. By the mid-1990s, his ready to wear business grossed about $9 million annually and his 97 licensing agreements had retail sales of more than $700 million a year. These included Bill Blass editions of the Ford Continental Mark automobiles.

Over the years he won three Coty American Fashion Critics Awards. The Council of Fashion Designers of America awarded him their Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987 and their Humanitarian Leadership Award in 1996. He was also named to the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame.

He became a philanthropist, giving $10 million to the New York Public Library in 1994, and bequeathing half of his $52 million estate, as well as several important ancient sculptures, to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

He presented his final collection in the fall of 1999, sold his company for $50 million, and retired to his 18th century home in New Preston, CT. His New York Times obituary says: "A man of robust but simple tastes who would go out of his way for a hamburger, Mr. Blass would serve guests his own meatloaf recipe, followed perhaps by lemon meringue pie. He always maintained, only partly in jest, "My claim to immortality will be my meatloaf."

The year after he retired, the lifetime smoker was diagnosed with oral cancer, and he died on June 12, 2002.

Sources:

1922 birth certificate

1940 census

1940 high school yearbook

1940 article in the Chicago Tribune re his prize in American Fashions competition

https://www.newspapers.com/image/369937128/?terms=bill%20blass&match=1

1942 draft card

1947 article in the Chicago Tribune re American Fashions competition

https://www.newspapers.com/image/371865239/?terms=bill%20blass&match=2

1947 article in Angola Herald (IN) re a poster he designed

https://www.newspapers.com/image/116157275/?terms=bill%20blass&match=1

2002 Social Security death index

2002 Find a Grave record; contains obituary

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6629241/bill-blass

2002 New York Times obituary

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/2002/06/13/522520.html?pageNumber=1

2013 article in the New York Times by Cathy Horyn, editor of his memoir

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/19/fashion/the-ghost-army-of-artists-and-designers.html

2020 Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites, Guest Blog

Wikipedia entry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Blass

Encyclopedia Britannica entry

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bill-Blass

GhostArmy.com website