Ghost Army in the News

This WWII 'Ghost Army' soldier tricked the Nazis. Now, the New Orleans professor will be honored.

New Orleans Times Picayune

Friday, February 23, 2024

On March 21, at the U.S. Capitol, a bygone company of American soldiers, most of whom are long dead, will be awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the country’s highest honors, in appreciation of their outstanding service in World War II.

What the so-called Ghost Army did 80 years ago went unheralded for decades, because it was all top secret.

The long-overdue award is being presented for a military success. But the Ghost Army was also an artistic triumph, maybe the greatest examples of trompe l'œil ever. And one of the artists who helped make it happen spent his long subsequent career in New Orleans.

Endless Experimentation

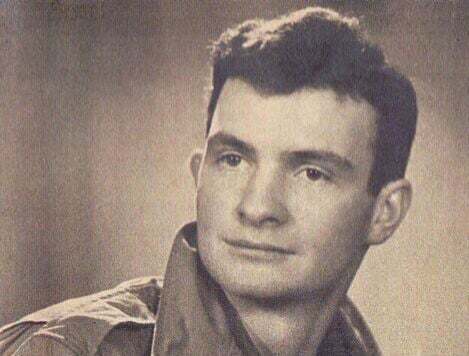

The late professor Jim Steg taught printmaking at Tulane University for 43 years. He was perfect for the job, because he was an expert at all aspects of the medium. Steg could demonstrate the centuries-old method of producing etchings by bathing copper plates in acid. But he also was well versed in newer, less exacting graphic art techniques.

Professor Steg famously pressed his own face on the glass pane of a Xerox machine to create grotesque self-portraits. Late in life, he produced one-of-a-kind miniature artworks by drawing directly on the emulsion of Polaroid photos.

His wife, Frances Swigart Steg, says that viewers giggled when they realized that some of the small photo drawings included erotic details.

Professor Steg encouraged experimentation among his students by experimenting himself. New Orleans artist Jan Gilbert — a great admirer of Steg — put it this way: “He gave students total freedom to embrace whatever tools and techniques you may need.”

Designed to be seen

A few years before Steg became a Tulane art teacher, he’d been involved in one of the great experiments of World War II, a project so hush-hush that he didn’t speak about it for decades.

Steg was one of the artistically inclined soldiers who volunteered to be part of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, legendarily known as the Ghost Army, a special group that devised ways to fool and confuse the Nazis on a grand scale.

Before big operations in Europe in 1944 and 1945, German reconnaissance pilots or advance scouts might spot an American column of tanks and artillery pieces that seemed to have popped up out of nowhere. Or the Germans might spy airplanes on a landing strip that suddenly appeared where none had been before.

There was no mistake. The Nazis had seen the enemy forces, they’d heard the chatter on the radio, they’d even heard the rumble of engines.

But they’d been duped.

The tanks and planes were fakes. They were inflatable replicas made just like Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade balloons. To say they materialized out of thin air wasn’t far wrong. The radio communication, the noise, was all a ruse.

Close up, the equipment might have looked a little soft and puffy. But the artists in the outfit had designed and painted up the balloon planes and tanks with enough authenticity that through binoculars or the lens of a high-altitude camera they could fool anybody. Steg and artists were called camouflage engineers, but their creations were really the opposite of camouflage. They were made to be seen.

Very hush-hush

The goal of the Ghost Army was simple. If the Germans were busy preparing to be attacked by fake tanks in one location, they weren’t getting ready for the real thing in another. It was brilliant. But it wasn’t anything anybody could brag about, because it remained top secret for years and years after the war, just in case the Army had to try the same trick again someday.

Steg’s wife said that in general her husband “kind of avoided memories of World War II, as many soldiers do.” And he shared very, very little about his role in the Ghost Army, even into the 1990s.

She said she’s not sure, but she thinks his specialty may have been producing deceptive shadowing on or around the inflated machinery. As she explained, from the time Steg was in high school, he’d had a love of theater. She suspects that phony tanks were just an extension of the deceptions of stage design.

The angst of humanity

While deployed in Europe during and after the war, Steg took every chance he could to sketch the images around him, particularly the war-weary faces of civilians and soldiers. Mrs. Steg said that he feared many of his models may not have ultimately survived. Steg, who died in 2001, kept his collection of war sketches through his entire 79 years.

Mrs. Steg said that if there was any theme that united her husband’s lifetime of artistic creation, it was “the angst of humanity” rendered in a way that was “dark but sensitive.”

Mrs. Steg, 82, plans to attend the ceremony on March 21. Only seven of the 1,000-plus members of the Ghost Army are still living.