23rd Headquarters Special Troops

Operation Brest

August 20-27, 1944

Inflatable tank at Operation Brest

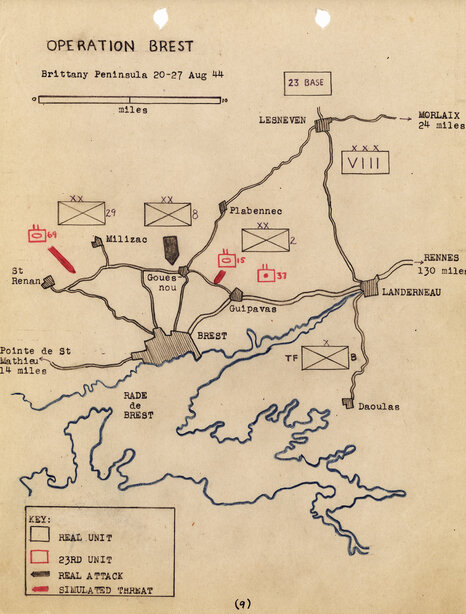

Operation BREST marked the first time the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops used visual, radio, and sonic deception altogether. It was one of the rare times that they found themselves in the midst of a major battle. Corporal Jack Masey, from Brooklyn New York, recalled that Brest as “the biggest piece of action I ever saw in World War II.”[i] And it was a learning experience that readied the deception troops for future operations in the months to come.

The soldiers of the Ghost Army used inflatable tanks, sound effects, and illusion to fool the Germans. Their mission at Brest was to inflate the apparent size of American forces attacking the city and help convince German General Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke to surrender. They also aimed to draw German forces to the flanks and away from the center, where American VIII Corps commander Troy Middleton planned to launch an assault on Friday, August 25. [iii] To accomplish this, they would pretend to be two tank battalions from the 6th Armored Division, which in reality had been withdrawn from Brest two weeks earlier, as well as a field artillery battalion.

Task Force X

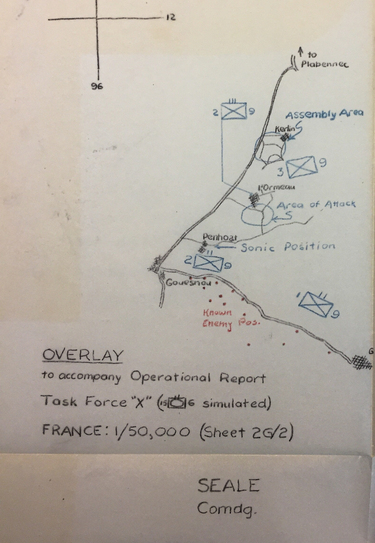

Patrols reconnoitered the area on Wednesday morning, August 23. Men from the 406th Combat Engineers came across a grisly scene: the wrecks of 15 halftracks, destroyed by German panzerfausts (bazookas). It was a grim reminder that they were in the middle of an active battlefield. [vi]

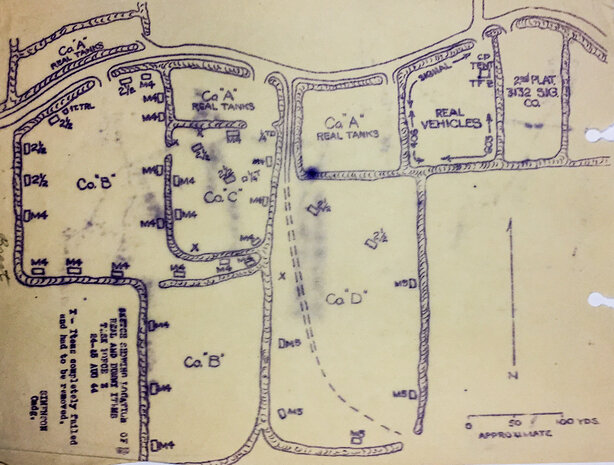

The bulk of the deception troops arrived that afternoon in the assembly position, near the hamlet of Kerlin. They set up 53 dummy tanks and several other vehicles. Company D of the 709th Tank Battalion was assigned to work with them. A light tank from the 709th laid down realistic tracks throughout the area. From 10:30 PM until past midnight, five halftracks equipped with wire recorders and oversize speakers played sounds of vehicles moving in. The sound effects began with one tank, then built in volume until the noise of a company of 18 tanks had been portrayed. They repeated this twice more to simulate the arrival of a second and third company. [vii] “Sound effects throughout the operation were extremely realistic,” said Capt. Bill Paden, an observer from the 2nd Infantry Division. “Such sounds as shifting of gears, tread noises, crackling of brush and voices of guides leading tanks into final positions could be clearly distinguished.” Paden praised the attention to detail. “Any interested observer within a 2.5 mile radius would have been convinced that a large number of vehicles was assembled . . . daylight investigation from a distance of 200 yards from the dummy positions would have apparently verified the presence of the tank battalion.” [viii]

That night, between 10 PM and 3 AM, the simulated tank companies deflated their dummies, moved forward to the “attack” position about a kilometer south to L’Ormeau, in the same area where the real 6th Armored had suffered major casualties August 8-9. (There is a monument to the 6th near that spot.) “Maintained items – tore them down at 9 PM,” scribbled Tompkins in the tiny diary he carried with him in violation of security regulations. “Moved up 500 yards to new area and set up 10 tanks.” He and his buddy, future fashion designer Bill Blass, didn’t get to set up their tent until 3 AM, at which point they promptly passed out with their feet sticking out into the pouring rain.

Meanwhile, Cpl. Al Albrecht, a 20-year old from Milwaukee Wisconsin serving in the 3132 Signal Company Special, drove his specially-equipped halftrack to a forward position just a few hundred meters from German lines, along with the crews of the other halftracks. They cranked up their 500-pound speaker arrays, and between 10:45 PM and 1:15 AM they played sounds of tanks moving up.[xi] The men felt extremely exposed. “I remember looking out there and saying ‘we’re pretty close to the enemy,’” said Albrecht. PFC Phil Dellisante described it as “like being on the firing line.” [xii]

The American attack went off the next day at 1 PM. PM. Bob Tompkins observed from the top of a hedgerow. “Fireworks start. Artillery raising hell” he wrote in his diary. “Saw shells landing about 400 yards in front of us. Could hear machine guns, rifles, mortars, etc. Saw time firing – saw 4 thunderbolts strafing with rockets. They roared over our heads and then dove into the thick of it. Havoc came over and bombed. Couple of mortar shells came our way. Landed about 50 yards behind us. Whole front line is one screen of smoke.” [xiii]

The enemy fire was evidence the deception had succeeded. But that very success had an unanticipated, tragic effect. Through a miscommunication or a misunderstanding of the deception’s impact, Company D of the 709th Tank Battalion joined the attack from near where The Ghost Army had focused the enemy’s attention. As a result, they were hit instantly with artillery fire. Five tanks were blown to bits. “Those guys never reached the line of departure,” recalled Cpl. Jarvie. “They just got decimated.”[xiv]

The incident weighed heavily on the men of the 23rd. Lt. Colonel Clifford Simenson, the unit’s operations officer, considered it a lesson on the crucial importance of careful coordination and communication. The tanks “should not have attacked in that place,” he later wrote in an analysis of the operation, “or otherwise the 23rd should have employed deception in another area.”

Task Force X pulled out that night, sonic trucks “playing” their departure to maintain the illusion. The next day, Tompkins made a last entry in his diary about the Battle of Brest. “Just beginning to realize how vulnerable we were the last three days as stories came in from various sources.”[xv]

Task Force Z

The 160 men of Task Force Z, commanded by Lt. Colonel Simenson, simulated the 69th Tank Battalion moving in to an area on the right flank about one kilometer northeast of Milizac. This deception was also supported by a company from the 709th Tank battalion, and sonic halftracks from the 603rd. It was similar in size and scope to the work of Task Force X, except that it was shorter in duration, two days instead of three. Officers who climbed the church steeple in Milizac to observe the display of inflatables could not tell difference between real tanks and fakes. A map below shows how Task Force Z dispersed its dummy vehicles. [xvi]

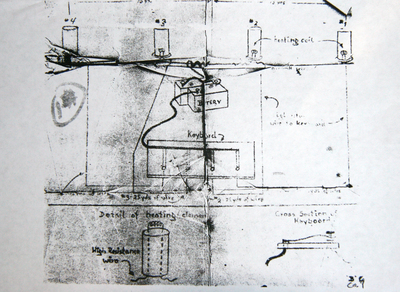

Task Force Y, commanded by Lt. Col John Mayo, had a very different mission to carry out. His men were positioned near Lannou, about 800 meters in front of the 37th Field Artillery Battalion. Their goal was to draw off counter-battery fire from the real artillery once the battle commenced on Friday the 25th. They were not using inflatables, but rather flash canisters to simulate the muzzle flashes of actual artillery. A telephone wire connected them to the fire direction center of the real battery, allowing the phony unit to co-ordinate their flashes with the actual artillery fire.

Anticipating enemy artillery fire, the men in the unit dug their foxholes deep and hunkered down. Enemy shells from big German coastal guns started pouring in half an hour after the attack started. “We definitely drew fire,” wrote Mayo.[xviii] “All hell seemed to be hurtling through the air,” commented Corporal Rolff Campbell of the 406th Combat Engineers. Most of the shells landed just in front of the fake artillery position. Some of the shrapnel pieces were “as big as a man’s arm,” wrote Campbell.[xix]No shells at all fell on the real artillery battery firing on the Germans – a strong indication that the deceivers accomplished their goal.

The deception did, indeed, achieve one of its objectives: Drawing German attention to the flanks. It did not, however, fulfill the larger mission of compelling the Germans to surrender. Neither did it weaken the center sufficiently for the Americans to end the siege with their attack on the 25th. German commander Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke had more troops than estimated, 38,000 instead of 21,000, and held out for 27 more days. It was generally agreed that, while the deception was well carried out, it was thwarted by the enemy’s lack of aerial observation and Ramcke’s fierce refusal to surrender under any circumstances.

Nevertheless, Operation Brest was a significant milestone for The Ghost Army. It was the first time all of its means of misdirection were brought to bear simultaneously, a baptism under fire that wiped out any idea that their mission would be some kind of lark. It honed their deception skills and taught them the urgent importance of co-ordination. Lessons learned at Brest made them battle-ready for critical deceptions missions to come.

Ghost Army Legacy Project President , and U.S. Consul for Western France Beth Webster stand at the historical marker in Plabennac

Below are some of the operation reports from this mission. The originals are in the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops records at the National Archives in College Park Maryland.

[i] Rick Beyer interview with Jack Masey, (Ghost Army Legacy Project Archive, 2007)

​

[ii] Martin Blumenson, The Patton Papers, p 532

[iii][i Frederick Fox. The Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. (US Army, 1945. National Archives)

[iv]Bob Tompins, World War II Diary, (unpublished, a transcription by Bill Blass’s mother is in the Ghost Army Legacy Project Archive)

[v] Fox

[vii] Capt. Oscar Seale, “Task Force X, Operational Report for Period 230715 Aug – 260115 Aug, 1944” (National Archives)

[viii] Capt. Bill Paden (Assistant Operations Officer, 2nd Division.) Inspection Report (Untitled) August 24, 1944 (National Archives)

[ix] Bob Tompkins interview with Rick Beyer, (Ghost Army Legacy Project Archive, 2007)

[x] Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles The Ghost Army of WWII (Princeton Architectural Press, 2015)

[xi] Seale; Also review of maps in the National Archives, and observations of Rick Beyer on location in June 2018.

[[xii] Al Albrecht, The Ghost Army of World War II (self published oral history video, VHS copy in Ghost Army Legacy Project Archive)

[xvi] Harold Deutsch (ed.) Basic Deception and the Normandy Invasion (Garland, 1989)

[xvii] Lt. Col John Mayo, “Report on Operation of Task Force Y (Brest) Aug 231400-261900” (National Archives, 1944)

[xxi] Colonel Cyrus Searcy, “Report on the Results of Deception Operaton at Brest” (National Archives, 1944)