23rd Headquarters Special Troops

23rd Overview

A member of the 603rd stands in front of an inflatable tank destroyer.

In the summer of 1944, a handpicked group of G.I.s landed in France to conduct a special mission. Armed with truckloads of inflatable tanks, a massive collection of sound effects records, and more than a few tricks up their sleeves, their job was to create a traveling road show of deception on the battlefields of Europe, with the German Army as their audience. From Normandy to the Rhine, the 1100 men of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, known as the Ghost Army, conjured up phony convoys, phantom divisions, and make-believe headquarters to fool the enemy about the strength and location of American units.

Each deception required that they impersonate a different (and vastly larger) U.S. unit. Like actors in a repertory theater, they would mount an ever-changing multimedia show tailored to each operation. The men immersed themselves in their roles, even hanging out at local cafes and spinning their counterfeit stories for spies who might lurk in the shadows. Painstakingly recorded sounds of armored and infantry units were blasted from sound trucks; radio operators created phony traffic nets; and inflatable tanks, trucks, artillery and even airplanes were imperfectly camouflaged so they would be visible to enemy reconnaissance.

Origin

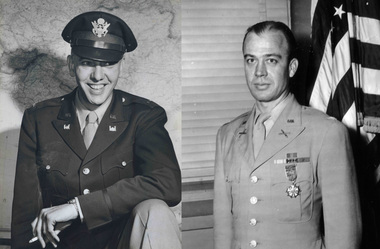

MAJ Ralph Ingersoll and COL Billy Harris

His boss at the Special Plans Branch was Colonel Billy Harris. Harris was a straight-arrow West Point graduate. His military roots ran deep: his mother introduced Dwight Eisenhower to his future bride, Mamie Dowd. Billy's father was a general. His uncle was a general. His brother became a general, and Billy eventually did too. During the Korean War Billy was commander of the 7th Cavalry – Custer’s old outfit.

Thrown together by war, these two very different men from the civilian and military worlds forged an amazingly fertile partnership. Ingersoll was the wild idea, pie-in-the sky guy. Harris was the feet on the ground “how do we make this work” guy.” Inspired by the British deceptions, especially Operation Bertram in North Africa, and wanting to give the American army every advantage they could when they went into France, these two planners dreamed up The Ghost Army and sold the idea to the top brass.

Order of Battle

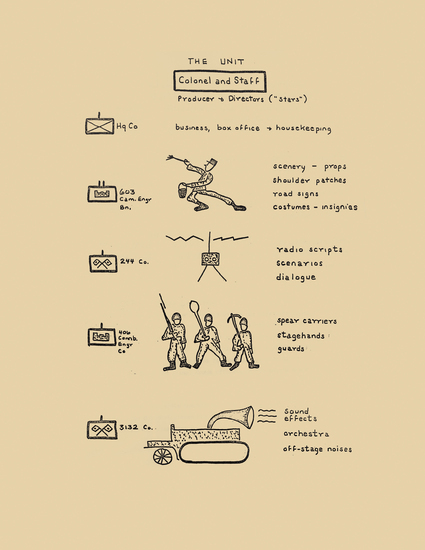

This illustration, by Lt. Fred Fox, shows the separate components of the 23rd and compares them to a theatrical company. "We must remember that we are playing to a very critical and attentive radio, ground, and aerial audience," he wrote. "They must all be convinced."

The 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion

The largest unit in The Ghost Army, its 379 men handled visual deception, using an array of inflatable rubber tanks, trucks, artillery, and jeeps to create a deceptive tableau for enemy aerial reconnaissance or distant observers. The unit had spent the previous two years doing camouflage work, and included in its ranks many artists specially recruited for that job.

The Signal Company Special

Formerly the 244th Signal Company, this group of 296 men carried out radio deception, also known as “spoof radio.” Operators created phony traffic nets, impersonating radio operators from real units. They mastered the art of mimicking an operator’s method of sending Morse code, so that the enemy would never catch on that the real unit and its radio operator were long gone.

The 3132 Signal Service Company

The 406th Engineer Combat Company

Led by Captain George Rebh, the 168 men of the 406th were trained as fighting soldiers. They provided perimeter security for the rest of Ghost Army. They also executed construction and demolition tasks including digging tank and artillery positions. The men of the 406th frequently used their bulldozers to simulate tank tracks as part of the visual deception.

War Diary

The 23rd Headquarters Special Troops staged more than 20 deception operations in France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany, often operating dangerously close to the front lines. “Its complement was more theatrical than military,” noted the unit’s official history. “It was like a traveling road show that went up and down the front lines impersonating the real fighting outfits.”

As the Allies moved inland through Normandy, as Patton broke out of the hedgerows and raced across France, as General Bradley ordered the relief of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge, the Ghost Army was there, playing an unsung role

In July 1944, Operation Brittany tricked the enemy about where General George Patton was headed, helping him to race across France and smash much of the German army.

In September, Operation Bettembourg helped held a dangerously undermanned part of Patton’s line as he was attacking the fortress city of Metz. “There is one rather bad spot in my line, but I don’t think the Huns know it” Patton wrote to his wife. “Hiding it now by the grace of God and a lot of guts

In December 1944, During the Battle of the Bulge, the unit conducted a radio-only deception, Operation Kodak, that helped draw German attention away from the effort to relieve Bastogne.

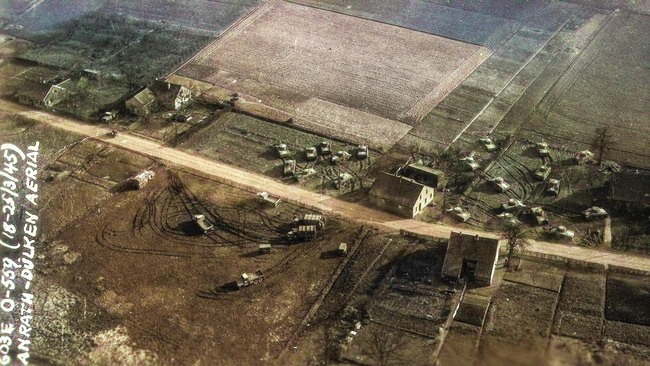

In March 1945, they put on a dazzling deception along the Rhine River, their biggest ever, Operation Viersen drew the enemy away from a real crossing by the 9th Army. They succeeded in fooling the Germans about when the 9th US Army would cross the Rhine, and are credited with saving thousands of lives in the bargain. It earned them a commendation from 9th Army commander William Simpson. Inflatable vehicles along the Rhine in March, 1945

Three Ghost Army soldiers were killed and dozens wounded carrying out their missions.

The details of the story remained classified until 1996. Thirty years after the war, when the details of their story were still being kept secret, a United States Army analyst who studied their missions came away deeply impressed with the impact of their illusions. “Rarely, if ever, has there been a group of such a few men which had so great an influence on the outcome of a major military campaign.”

Unofficial Insignia of the 23rd Headquarters Special troops, which appears on their Official History written in 1945.