23rd Headquarters Special Troops

Operation Bettembourg

September 15 -22, 1944

Operation BETTEMBOURG was thrown together in a hurry, and then stretched into the longest deception operation that the 23rd HQ Special Troops conducted during the war. For more than a week, the 23rd helped defend a dangerously undermanned section of the Third Army’s front line, stretching more than twenty miles. Ghost Army Operations Officer Col. Clifford Simenson considered it a turning point for the unit: “It was our first operation that was executed fully professionally and correctly.”[i] And a major part of the operation was conducted inside the commune of Bettembourg.

On Friday, September 14, 1944, the 23rd was bivouacked outside Paris, in St. Germain-en-Laye. That morning, its commander, Colonel Harry Reeder, received word that the unit was being called on to conduct a mission. By noon the men had been put on alert and Reeder was meeting with officers from the 12th US Army Group Special Plans Branch in Versailles. They informed him that General Walton Walker’s XXth Corps, part of General George Patton’s Third Army, wanted the 23d to project the presence of an Armored division along the Moselle River as soon as possible. About half the unit was designated to carry off the deception. They pulled out at 4 PM to head to the front, more than 200 miles away.[ii]

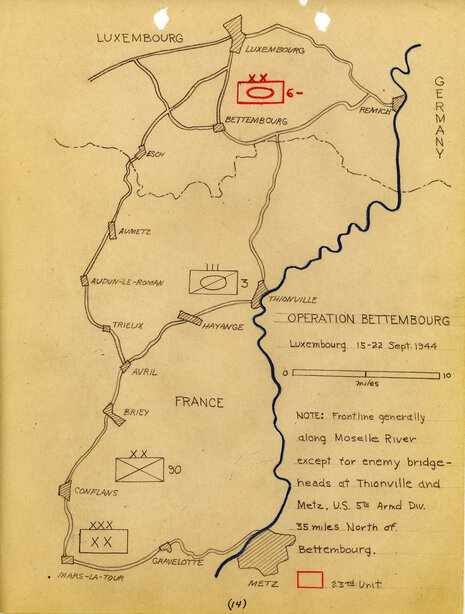

Patton’s Third Army was attacking the fortress city of Metz. Between Metz and Luxembourg City, more than 25 miles of the American front line was thinly held by a squadron of the Third Armored Cavalry under Colonel James Polk. The front ran roughly along the Moselle River, although the Germans had several bridgeheads, including one at Remich.[iii]The mission of the 23rd was to impersonate elements of the 6th Armored Division, and make it seem as if they were reinforcing this part of the line. About 500 men would pretend to be 8000. The objective was to draw enemy units away from Metz, and also to keep the enemy from realizing how thinly held this sector was.[iv]

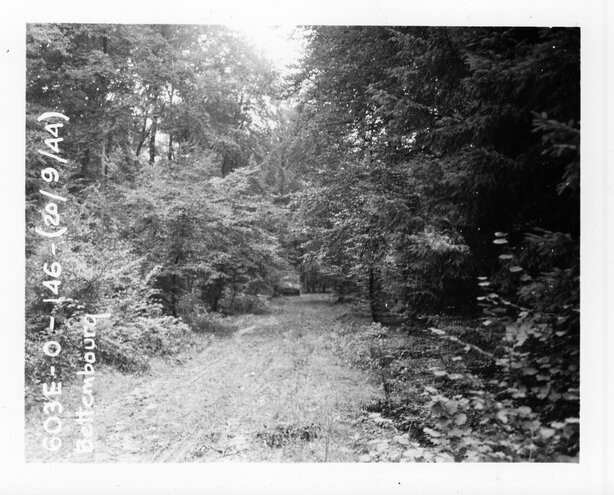

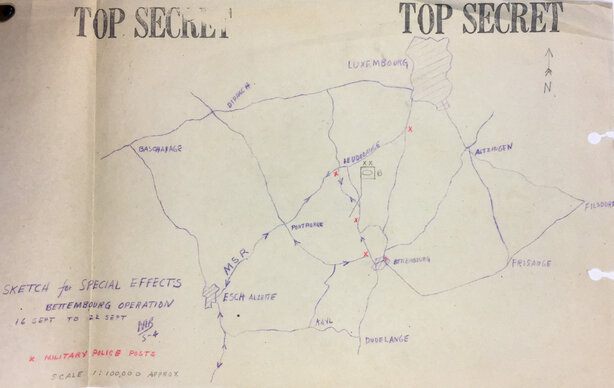

The men from the Ghost Army were impersonating two brigade-sized units from the 6th Armored, Combat Command A (CCA) and Combat Command Reserve (CCR), as well as the division headquarters.[v] The units portraying CCA pulled into a heavily wooded area in Bettembourg, just north of the village of Abweiler, at about 4PM on the afternoon of Saturday September15.[vi] ( They included one and a half companies from the 603rd camouflage Engineers, a platoon from the 406th Combat Engineers, and detachments from 3132 Signal Service Company and the Signal Company. They were under the command of Lt. Colonel Edgar Schroeder. CCR was situated about two miles away, in the northern part of the commune of Roeser, under the command of Captain Oscar Seale.

Plans were quickly made. Ghost Army soldiers in the woods north of Abweiler set up a dozen inflatable M4 Sherman tanks in the woods that night.

Meantime, after a planning meeting at 6:30 PM, sonic trucks put on a hastily conceived show from 10 PM to midnight playing the sounds of an armored division moving in. [vii][viii]

Lieutenant Dick Syracuse’s platoon was manning a security perimeter around the sound trucks as they played their concert of tank sounds. Then, as Syracuse remembered it, a colonel from the cavalry unit came “storming up the road. This guy looked like a monster because he had a flak jacket on, and there were hand grenades hanging, and [he was] carrying a Thompson submachine gun.”

“What the hell is going on here, son?”

“What do you mean, Colonel?” replied Syracuse.

“What are those tanks doing there?”

Syracuse tried to explain that there were no tanks actually there. The response was a string of expletives.

“Don’t tell me that! I know what I hear! There are tanks out there, and nobody told me there was going to be tanks here!” Things were eventually straightened out. It developed that the colonel had missed the briefing where the deception was explained, and his aide had not had time to tell him about it yet. His parting words to Syracuse were, “Well, son, you certainly could have fooled me.”[ix]

Radio operators set up a phony radio network for the notional (fake) division on the night of the 15th. They eventually had ten radios operating, transmitting back and forth, and also transmitting to real radio networks being run by 3rd Cavalry, XX Corps, and other nearby units on their flanks. [x]

The next morning, Sunday September 16, the men lit fires to simulate the presence of an armored division cooking breakfast. They painted 6th Armored markings on their vehicles, while the factory section churned out fake Sixth Armored shoulder patches that they sewed on their uniforms. All of the men were given a short history of the Sixth Armored Division. Men were sent in Bettemborg and other nearby towns, pretending to be on recreation leave, where they could be overheard talking about their division in cafes and bars. A water point was put in sight of the Bettembourg town center, and trucks came back and forth as if gathering water for the 8000 men who would have moved in with the 6th Armored.

Soldiers from the 406th Combat Engineers guarded intersections in Bettembourg, Leeudeldange, and the road in between, dressed as MPs from the Sixth Armored. All these “special effects” ploys had the intended effect.[xi] “Civilians were observed photographing bumpers, taking notes, and asking ‘friendly’ questions,” wrote Lieutenant Colonel Clifford Simenson.[xii]

The dummies set up in the woods north of Abweiler stayed up for 24 hours. But an incident took place that raised security concerns. A civilian in a buggy rode by as four enlisted men were carrying one of the inflatable dummies in sight of the road. It was decided soon afterward that the dummies would be taken down for fear that German infiltrators might see them. [xiii]

Operation Bettembourg was originally planned to last for only two days, until the Eighty-Third Infantry Division could arrive to fill the hole. But the Eighty-Third was delayed, so the deception stretched out for day after perilous day. Every passing hour increased the odds that the Germans might see through the fakery. As Lieutenant Bob Conrad put it, there was nothing between the Ghost Army and the Germans “but our hopes and prayers.”[xiv] If the Germans saw through the deceptions, they might have been able to break through and attack Patton’s forces from behind.

The mood grew tense. “German units were spotted moving in across the river, presumably to defend against the Sixth Armored Division. German patrols continued to be a worry. “Heinie patrol reported about three or four miles away,” wrote Sgt. Bob Tompkins in his diary on Friday, September 21. “Civilians seem to be getting too anxious about our set-up. We should have moved out a couple of days ago, but attack seems imminent so I guess we have orders to remain until it begins”[xv]. Major Ralph Ingersoll of the 12th US Army Group Special Plans branch visited to pass on a warning. The enemy was regrouping and becoming more aggressive. Civilians Luxembourgers reported seeing Germans in nearby woods. Shots were heard. Telephone wires laid by the Signal Company were found cut.[xvi]

Finally, on Saturday, September 22nd, the 83rd Infantry was ready to move in to hold the line for real. To preserve the deception, the sonic trucks carefully played the sounds of tanks moving away as the fake Sixth Armored division pulled out in the night. Soon they were in Luxembourg City. The operation was judged a success. Patton’s line had held, and after eight days along the front, the Ghost Army slipped away.[ix]

The story of the Ghost Army was kept secret for more than fifty years after World War II. Since their exploits were kept under wraps, accounts of actions they took part in often erase their role. Take, for example, a brief history of the 3rd Cavalry published at the end of the war. It described those weeks along the Moselle this way.

“During this time, the handful of men (760) in this squadron [43rd Cavalry Squadron] kicked up such a fuss with the help of supporting artillery, that the German G-2’s reported everything from an armored combat command to several divisions in the 23 mile front zone.”[xx]

But the official after-action report of the 3rd Cav gave credit where credit was due: "The establishment of a "simulated armored division" during this period by 23 Hq Special Troops . . . added to the bewilderment of the enemy as to our strength. All indications pointed to the fact that he thought we were in great strength in this sector, as he continued to increase his forces along the river to counter-attack our "armored thrust." [xx]Another great review for the Ghost Army.

[i] Account of Operation Bettembourg by Clifford Simenonson, Clifford G. Simenson Papers, US Army Military History Center, Carlisle PA

[ii] Report of Operation Bettembourg, 15-22 September 1944, dated October 14, by Lt. Colonel James Snee

[iii] Polk, James; World War II Letters and Notes of Colonel James H. Polk, p 87

[iv] Fox Fred; Fred’s World, unpublished manuscript in the possession of his son, Donald Fox. Also, Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, National Archives

[v] Combat Command “A” Operation Bettembourg, Repot by Lt. Col. E.W. Scroeder, National Archives

[vi] The evidene that CCA was in the woods north of Abweiler is overhwhelming. Most important are the multiple map overlays found in the files of the 23rd at the National Archives. Once laid over the appropriate US Army maps, they clearly show the locations for the troops in CCA, CCR and the (fake) 6th Armored Division HQ. Also, according to an unpublished history of the 406th Engineers, a copy of which is in the Ghost Army Legacy Project archive, they bivouaced “one mile north of Abweiler.”

[vii] Combat Command “A” Operation Bettembourg, Report by Lt. Col. E.W. Scroeder, National Archives

[viii] “Report of Sonic Operation Bettembourg; 15-22 September by Robert Hiller, dated October 15, 1944, National Archives

[ix] Author interview with Richard Syracuse, 2006

[x] “Signal Report on Operation Bettembourg”, dated 12 October 1944, National Archives

[xi] “Summaryof Special Effects for Operation Bettembourg” by Major David Bridges, National Archives

[xii] Account of Operation Bettembourg by Clifford Simenonson, CLiford G. Simenson Papers, US Army Military History Center, Carlisle PA

[xiii] Journal of activiies during Operation bettembourg, found in National Archives, author unknown (first page is missing.) Also, LUXEMBURG BEFREIUNG UND ARDENNEN OFFENSIVE 1944-1945" from E.T.MELCHERS . 1981 Sankt-Paulus-Druckerei..(Editions du Centre, J.-P.Krippler-Müller, 1959.)

[xiv] Author interview with Bob Conrad

[xv] Diary of Bob Tomkins, entry dated September 21, 1944. A copy of the diary is in the Ghost Army Legacay Project Archives

[xvi] Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops

[xvii] Blumenson, Martin, editor, The Patton Papers 1940-1945 p 552.

[xviii] Polk, James; World War II Letters and Notes of Colonel James H. Polk, p 90

[xix] “Report of Sonic Operation Bettembourg; 15-22 September by Robert Hiller, dated October 15, 1944, National Archives, Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, National Archives

[xx] “Brief history of the 43rd Cavalry Rcn Sq (Metz)” taken from the Bowie Blade, Camp Bowie TX, 31st August 1945 issue.