23rd Headquarters Special Troops

23rd Overview

A member of the 603rd stands in front of an inflatable tank destroyer.

In the summer of 1944, a handpicked group of G.I.s landed in France to conduct a special mission. Armed with truckloads of inflatable tanks, a massive collection of sound effects records, and more than a few tricks up their sleeves, their job was to create a traveling road show of deception on the battlefields of Europe, with the German Army as their audience. From Normandy to the Rhine, the 1100 men of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, known as the Ghost Army, conjured up phony convoys, phantom divisions, and make-believe headquarters to fool the enemy about the strength and location of American units.

Each deception required that they impersonate a different (and vastly larger) U.S. unit. Like actors in a repertory theater, they would mount an ever-changing multimedia show tailored to each operation. The men immersed themselves in their roles, even hanging out at local cafes and spinning their counterfeit stories for spies who might lurk in the shadows. Painstakingly recorded sounds of armored and infantry units were blasted from sound trucks; radio operators created phony traffic nets; and inflatable tanks, trucks, artillery and even airplanes were imperfectly camouflaged so they would be visible to enemy reconnaissance.

Origin

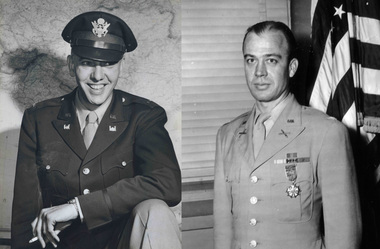

MAJ Ralph Ingersoll and COL Billy Harris

His boss at the Special Plans Branch was Colonel Billy Harris. Harris was a straight-arrow West Point graduate. His military roots ran deep: his mother introduced Dwight Eisenhower to his future bride, Mamie Dowd. Billy's father was a general. His uncle was a general. His brother became a general, and Billy eventually did too. During the Korean War Billy was commander of the 7th Cavalry – Custer’s old outfit.

Thrown together by war, these two very different men from the civilian and military worlds forged an amazingly fertile partnership. Ingersoll was the wild idea, pie-in-the sky guy. Harris was the feet on the ground “how do we make this work” guy.” Inspired by the British deceptions, especially Operation Bertram in North Africa, and wanting to give the American army every advantage they could when they went into France, these two planners dreamed up The Ghost Army and sold the idea to the top brass.

Order of Battle

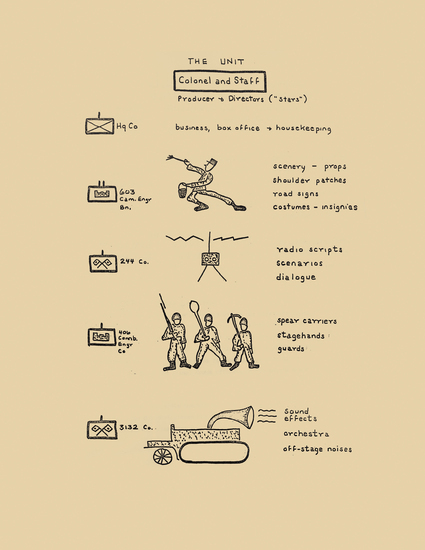

This illustration, by Lt. Fred Fox, shows the separate components of the 23rd and compares them to a theatrical company. "We must remember that we are playing to a very critical and attentive radio, ground, and aerial audience," he wrote. "They must all be convinced."

The 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion

The largest unit in The Ghost Army, its 379 men handled visual deception, using an array of inflatable rubber tanks, trucks, artillery, and jeeps to create a deceptive tableau for enemy aerial reconnaissance or distant observers. The unit had spent the previous two years doing camouflage work, and included in its ranks many artists specially recruited for that job.

The Signal Company Special

Formerly the 244th Signal Company, this group of 296 men carried out radio deception, also known as “spoof radio.” Operators created phony traffic nets, impersonating radio operators from real units. They mastered the art of mimicking an operator’s method of sending Morse code, so that the enemy would never catch on that the real unit and its radio operator were long gone.

The 3132 Signal Service Company

The 406th Engineer Combat Company

Led by Captain George Rebh, the 168 men of the 406th were trained as fighting soldiers. They provided perimeter security for the rest of Ghost Army. They also executed construction and demolition tasks including digging tank and artillery positions. The men of the 406th frequently used their bulldozers to simulate tank tracks as part of the visual deception.

War Diary

The 23rd Headquarters Special Troops staged more than 20 deception operations in France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany, often operating dangerously close to the front lines. “Its complement was more theatrical than military,” noted the unit’s official history. “It was like a traveling road show that went up and down the front lines impersonating the real fighting outfits.”

As the Allies moved inland through Normandy, as Patton broke out of the hedgerows and raced across France, as General Bradley ordered the relief of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge, the Ghost Army was there, playing an unsung role

In July 1944, Operation Brittany tricked the enemy about where General George Patton was headed, helping him to race across France and smash much of the German army.

In September, Operation Bettembourg helped held a dangerously undermanned part of Patton’s line as he was attacking the fortress city of Metz. “There is one rather bad spot in my line, but I don’t think the Huns know it” Patton wrote to his wife. “Hiding it now by the grace of God and a lot of guts

In December 1944, During the Battle of the Bulge, the unit conducted a radio-only deception, Operation Kodak, that helped draw German attention away from the effort to relieve Bastogne.

In March 1945, they put on a dazzling deception along the Rhine River, their biggest ever, Operation Viersen drew the enemy away from a real crossing by the 9th Army. They succeeded in fooling the Germans about when the 9th US Army would cross the Rhine, and are credited with saving thousands of lives in the bargain. It earned them a commendation from 9th Army commander William Simpson. Inflatable vehicles along the Rhine in March, 1945

Three Ghost Army soldiers were killed and dozens wounded carrying out their missions.

The details of the story remained classified until 1996. Thirty years after the war, when the details of their story were still being kept secret, a United States Army analyst who studied their missions came away deeply impressed with the impact of their illusions. “Rarely, if ever, has there been a group of such a few men which had so great an influence on the outcome of a major military campaign.”​

Unofficial Insignia of the 23rd Headquarters Special troops, which appears on their Official History written in 1945.

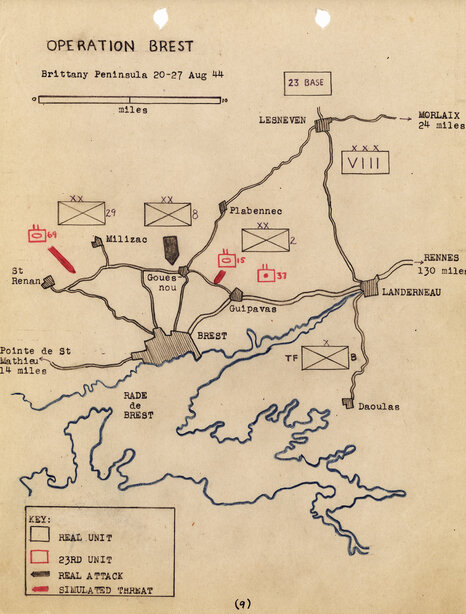

Operation Brest

August 20-27, 1944

Inflatable tank at Operation Brest

Operation BREST marked the first time the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops used visual, radio, and sonic deception altogether. It was one of the rare times that they found themselves in the midst of a major battle. Corporal Jack Masey, from Brooklyn New York, recalled that Brest as “the biggest piece of action I ever saw in World War II.”[i] And it was a learning experience that readied the deception troops for future operations in the months to come.

The soldiers of the Ghost Army used inflatable tanks, sound effects, and illusion to fool the Germans. Their mission at Brest was to inflate the apparent size of American forces attacking the city and help convince German General Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke to surrender. They also aimed to draw German forces to the flanks and away from the center, where American VIII Corps commander Troy Middleton planned to launch an assault on Friday, August 25. [iii] To accomplish this, they would pretend to be two tank battalions from the 6th Armored Division, which in reality had been withdrawn from Brest two weeks earlier, as well as a field artillery battalion.

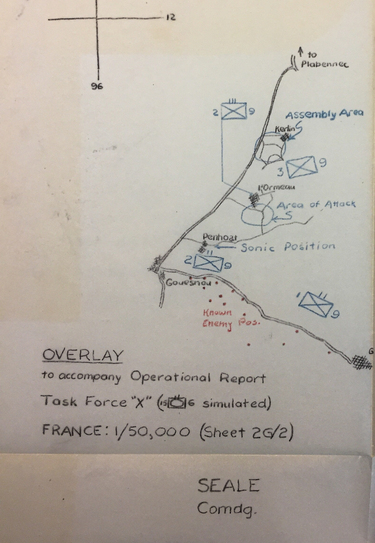

Task Force X

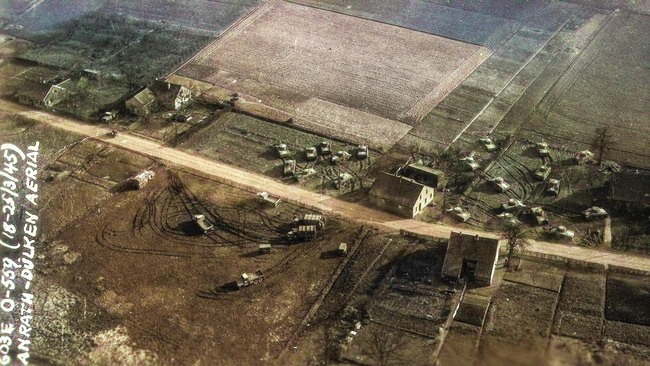

Patrols reconnoitered the area on Wednesday morning, August 23. Men from the 406th Combat Engineers came across a grisly scene: the wrecks of 15 halftracks, destroyed by German panzerfausts (bazookas). It was a grim reminder that they were in the middle of an active battlefield. [vi]

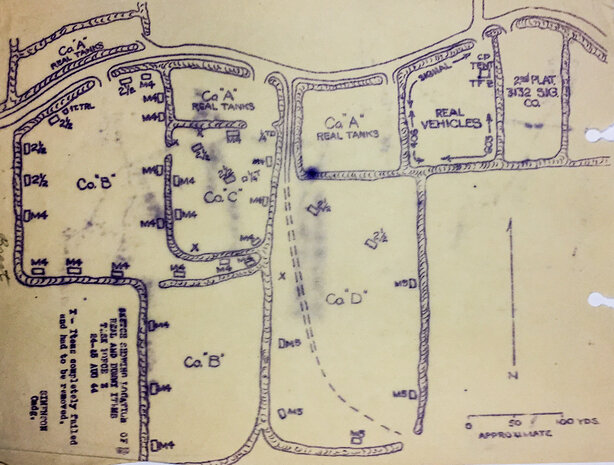

The bulk of the deception troops arrived that afternoon in the assembly position, near the hamlet of Kerlin. They set up 53 dummy tanks and several other vehicles. Company D of the 709th Tank Battalion was assigned to work with them. A light tank from the 709th laid down realistic tracks throughout the area. From 10:30 PM until past midnight, five halftracks equipped with wire recorders and oversize speakers played sounds of vehicles moving in. The sound effects began with one tank, then built in volume until the noise of a company of 18 tanks had been portrayed. They repeated this twice more to simulate the arrival of a second and third company. [vii] “Sound effects throughout the operation were extremely realistic,” said Capt. Bill Paden, an observer from the 2nd Infantry Division. “Such sounds as shifting of gears, tread noises, crackling of brush and voices of guides leading tanks into final positions could be clearly distinguished.” Paden praised the attention to detail. “Any interested observer within a 2.5 mile radius would have been convinced that a large number of vehicles was assembled . . . daylight investigation from a distance of 200 yards from the dummy positions would have apparently verified the presence of the tank battalion.” [viii]

That night, between 10 PM and 3 AM, the simulated tank companies deflated their dummies, moved forward to the “attack” position about a kilometer south to L’Ormeau, in the same area where the real 6th Armored had suffered major casualties August 8-9. (There is a monument to the 6th near that spot.) “Maintained items – tore them down at 9 PM,” scribbled Tompkins in the tiny diary he carried with him in violation of security regulations. “Moved up 500 yards to new area and set up 10 tanks.” He and his buddy, future fashion designer Bill Blass, didn’t get to set up their tent until 3 AM, at which point they promptly passed out with their feet sticking out into the pouring rain.

Meanwhile, Cpl. Al Albrecht, a 20-year old from Milwaukee Wisconsin serving in the 3132 Signal Company Special, drove his specially-equipped halftrack to a forward position just a few hundred meters from German lines, along with the crews of the other halftracks. They cranked up their 500-pound speaker arrays, and between 10:45 PM and 1:15 AM they played sounds of tanks moving up.[xi] The men felt extremely exposed. “I remember looking out there and saying ‘we’re pretty close to the enemy,’” said Albrecht. PFC Phil Dellisante described it as “like being on the firing line.” [xii]

The American attack went off the next day at 1 PM. PM. Bob Tompkins observed from the top of a hedgerow. “Fireworks start. Artillery raising hell” he wrote in his diary. “Saw shells landing about 400 yards in front of us. Could hear machine guns, rifles, mortars, etc. Saw time firing – saw 4 thunderbolts strafing with rockets. They roared over our heads and then dove into the thick of it. Havoc came over and bombed. Couple of mortar shells came our way. Landed about 50 yards behind us. Whole front line is one screen of smoke.” [xiii]

The enemy fire was evidence the deception had succeeded. But that very success had an unanticipated, tragic effect. Through a miscommunication or a misunderstanding of the deception’s impact, Company D of the 709th Tank Battalion joined the attack from near where The Ghost Army had focused the enemy’s attention. As a result, they were hit instantly with artillery fire. Five tanks were blown to bits. “Those guys never reached the line of departure,” recalled Cpl. Jarvie. “They just got decimated.”[xiv]

The incident weighed heavily on the men of the 23rd. Lt. Colonel Clifford Simenson, the unit’s operations officer, considered it a lesson on the crucial importance of careful coordination and communication. The tanks “should not have attacked in that place,” he later wrote in an analysis of the operation, “or otherwise the 23rd should have employed deception in another area.”

Task Force X pulled out that night, sonic trucks “playing” their departure to maintain the illusion. The next day, Tompkins made a last entry in his diary about the Battle of Brest. “Just beginning to realize how vulnerable we were the last three days as stories came in from various sources.”[xv]

Task Force Z

The 160 men of Task Force Z, commanded by Lt. Colonel Simenson, simulated the 69th Tank Battalion moving in to an area on the right flank about one kilometer northeast of Milizac. This deception was also supported by a company from the 709th Tank battalion, and sonic halftracks from the 603rd. It was similar in size and scope to the work of Task Force X, except that it was shorter in duration, two days instead of three. Officers who climbed the church steeple in Milizac to observe the display of inflatables could not tell difference between real tanks and fakes. A map below shows how Task Force Z dispersed its dummy vehicles. [xvi]

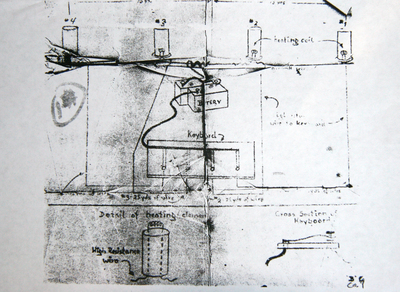

Task Force Y, commanded by Lt. Col John Mayo, had a very different mission to carry out. His men were positioned near Lannou, about 800 meters in front of the 37th Field Artillery Battalion. Their goal was to draw off counter-battery fire from the real artillery once the battle commenced on Friday the 25th. They were not using inflatables, but rather flash canisters to simulate the muzzle flashes of actual artillery. A telephone wire connected them to the fire direction center of the real battery, allowing the phony unit to co-ordinate their flashes with the actual artillery fire.

Anticipating enemy artillery fire, the men in the unit dug their foxholes deep and hunkered down. Enemy shells from big German coastal guns started pouring in half an hour after the attack started. “We definitely drew fire,” wrote Mayo.[xviii] “All hell seemed to be hurtling through the air,” commented Corporal Rolff Campbell of the 406th Combat Engineers. Most of the shells landed just in front of the fake artillery position. Some of the shrapnel pieces were “as big as a man’s arm,” wrote Campbell.[xix]No shells at all fell on the real artillery battery firing on the Germans – a strong indication that the deceivers accomplished their goal.

The deception did, indeed, achieve one of its objectives: Drawing German attention to the flanks. It did not, however, fulfill the larger mission of compelling the Germans to surrender. Neither did it weaken the center sufficiently for the Americans to end the siege with their attack on the 25th. German commander Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke had more troops than estimated, 38,000 instead of 21,000, and held out for 27 more days. It was generally agreed that, while the deception was well carried out, it was thwarted by the enemy’s lack of aerial observation and Ramcke’s fierce refusal to surrender under any circumstances.

Nevertheless, Operation Brest was a significant milestone for The Ghost Army. It was the first time all of its means of misdirection were brought to bear simultaneously, a baptism under fire that wiped out any idea that their mission would be some kind of lark. It honed their deception skills and taught them the urgent importance of co-ordination. Lessons learned at Brest made them battle-ready for critical deceptions missions to come.

Ghost Army Legacy Project President , and U.S. Consul for Western France Beth Webster stand at the historical marker in Plabennac

Below are some of the operation reports from this mission. The originals are in the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops records at the National Archives in College Park Maryland.

[i] Rick Beyer interview with Jack Masey, (Ghost Army Legacy Project Archive, 2007)

​

[ii] Martin Blumenson, The Patton Papers, p 532

[iii][i Frederick Fox. The Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. (US Army, 1945. National Archives)

[iv]Bob Tompins, World War II Diary, (unpublished, a transcription by Bill Blass’s mother is in the Ghost Army Legacy Project Archive)

[v] Fox

[vii] Capt. Oscar Seale, “Task Force X, Operational Report for Period 230715 Aug – 260115 Aug, 1944” (National Archives)

[viii] Capt. Bill Paden (Assistant Operations Officer, 2nd Division.) Inspection Report (Untitled) August 24, 1944 (National Archives)

[ix] Bob Tompkins interview with Rick Beyer, (Ghost Army Legacy Project Archive, 2007)

[x] Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles The Ghost Army of WWII (Princeton Architectural Press, 2015)

[xi] Seale; Also review of maps in the National Archives, and observations of Rick Beyer on location in June 2018.

[[xii] Al Albrecht, The Ghost Army of World War II (self published oral history video, VHS copy in Ghost Army Legacy Project Archive)

[xvi] Harold Deutsch (ed.) Basic Deception and the Normandy Invasion (Garland, 1989)

[xvii] Lt. Col John Mayo, “Report on Operation of Task Force Y (Brest) Aug 231400-261900” (National Archives, 1944)

[xxi] Colonel Cyrus Searcy, “Report on the Results of Deception Operaton at Brest” (National Archives, 1944)

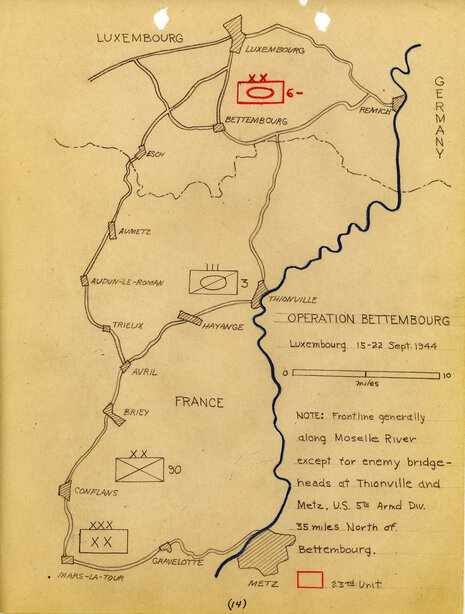

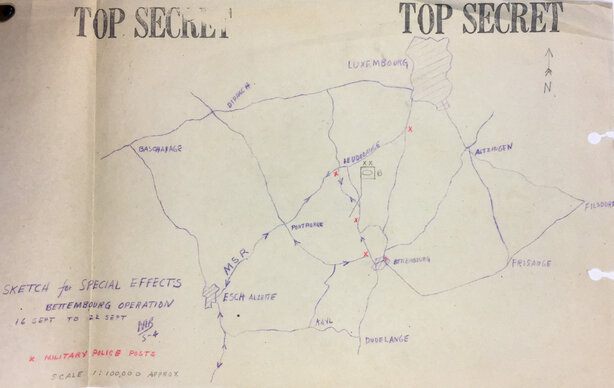

Operation Bettembourg

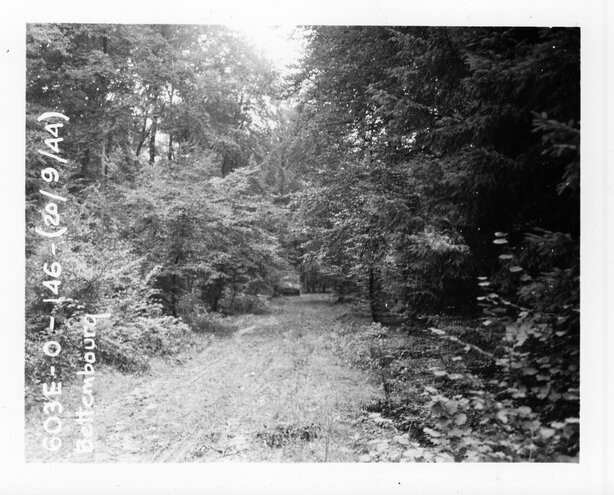

September 15 -22, 1944

Operation BETTEMBOURG was thrown together in a hurry, and then stretched into the longest deception operation that the 23rd HQ Special Troops conducted during the war. For more than a week, the 23rd helped defend a dangerously undermanned section of the Third Army’s front line, stretching more than twenty miles. Ghost Army Operations Officer Col. Clifford Simenson considered it a turning point for the unit: “It was our first operation that was executed fully professionally and correctly.”[i] And a major part of the operation was conducted inside the commune of Bettembourg.

On Friday, September 14, 1944, the 23rd was bivouacked outside Paris, in St. Germain-en-Laye. That morning, its commander, Colonel Harry Reeder, received word that the unit was being called on to conduct a mission. By noon the men had been put on alert and Reeder was meeting with officers from the 12th US Army Group Special Plans Branch in Versailles. They informed him that General Walton Walker’s XXth Corps, part of General George Patton’s Third Army, wanted the 23d to project the presence of an Armored division along the Moselle River as soon as possible. About half the unit was designated to carry off the deception. They pulled out at 4 PM to head to the front, more than 200 miles away.[ii]

Patton’s Third Army was attacking the fortress city of Metz. Between Metz and Luxembourg City, more than 25 miles of the American front line was thinly held by a squadron of the Third Armored Cavalry under Colonel James Polk. The front ran roughly along the Moselle River, although the Germans had several bridgeheads, including one at Remich.[iii]The mission of the 23rd was to impersonate elements of the 6th Armored Division, and make it seem as if they were reinforcing this part of the line. About 500 men would pretend to be 8000. The objective was to draw enemy units away from Metz, and also to keep the enemy from realizing how thinly held this sector was.[iv]

The men from the Ghost Army were impersonating two brigade-sized units from the 6th Armored, Combat Command A (CCA) and Combat Command Reserve (CCR), as well as the division headquarters.[v] The units portraying CCA pulled into a heavily wooded area in Bettembourg, just north of the village of Abweiler, at about 4PM on the afternoon of Saturday September15.[vi] ( They included one and a half companies from the 603rd camouflage Engineers, a platoon from the 406th Combat Engineers, and detachments from 3132 Signal Service Company and the Signal Company. They were under the command of Lt. Colonel Edgar Schroeder. CCR was situated about two miles away, in the northern part of the commune of Roeser, under the command of Captain Oscar Seale.

Plans were quickly made. Ghost Army soldiers in the woods north of Abweiler set up a dozen inflatable M4 Sherman tanks in the woods that night.

Meantime, after a planning meeting at 6:30 PM, sonic trucks put on a hastily conceived show from 10 PM to midnight playing the sounds of an armored division moving in. [vii][viii]

​Lieutenant Dick Syracuse’s platoon was manning a security perimeter around the sound trucks as they played their concert of tank sounds. Then, as Syracuse remembered it, a colonel from the cavalry unit came “storming up the road. This guy looked like a monster because he had a flak jacket on, and there were hand grenades hanging, and [he was] carrying a Thompson submachine gun.”

“What the hell is going on here, son?”

“What do you mean, Colonel?” replied Syracuse.

“What are those tanks doing there?”

Syracuse tried to explain that there were no tanks actually there. The response was a string of expletives.

“Don’t tell me that! I know what I hear! There are tanks out there, and nobody told me there was going to be tanks here!” Things were eventually straightened out. It developed that the colonel had missed the briefing where the deception was explained, and his aide had not had time to tell him about it yet. His parting words to Syracuse were, “Well, son, you certainly could have fooled me.”[ix]

​​Radio operators set up a phony radio network for the notional (fake) division on the night of the 15th. They eventually had ten radios operating, transmitting back and forth, and also transmitting to real radio networks being run by 3rd Cavalry, XX Corps, and other nearby units on their flanks. [x]

The next morning, Sunday September 16, the men lit fires to simulate the presence of an armored division cooking breakfast. They painted 6th Armored markings on their vehicles, while the factory section churned out fake Sixth Armored shoulder patches that they sewed on their uniforms. All of the men were given a short history of the Sixth Armored Division. Men were sent in Bettemborg and other nearby towns, pretending to be on recreation leave, where they could be overheard talking about their division in cafes and bars. A water point was put in sight of the Bettembourg town center, and trucks came back and forth as if gathering water for the 8000 men who would have moved in with the 6th Armored.

​Soldiers from the 406th Combat Engineers guarded intersections in Bettembourg, Leeudeldange, and the road in between, dressed as MPs from the Sixth Armored. All these “special effects” ploys had the intended effect.[xi] “Civilians were observed photographing bumpers, taking notes, and asking ‘friendly’ questions,” wrote Lieutenant Colonel Clifford Simenson.[xii]

The dummies set up in the woods north of Abweiler stayed up for 24 hours. But an incident took place that raised security concerns. A civilian in a buggy rode by as four enlisted men were carrying one of the inflatable dummies in sight of the road. It was decided soon afterward that the dummies would be taken down for fear that German infiltrators might see them. [xiii]

Operation Bettembourg was originally planned to last for only two days, until the Eighty-Third Infantry Division could arrive to fill the hole. But the Eighty-Third was delayed, so the deception stretched out for day after perilous day. Every passing hour increased the odds that the Germans might see through the fakery. As Lieutenant Bob Conrad put it, there was nothing between the Ghost Army and the Germans “but our hopes and prayers.”[xiv] If the Germans saw through the deceptions, they might have been able to break through and attack Patton’s forces from behind.

The mood grew tense. “German units were spotted moving in across the river, presumably to defend against the Sixth Armored Division. German patrols continued to be a worry. “Heinie patrol reported about three or four miles away,” wrote Sgt. Bob Tompkins in his diary on Friday, September 21. “Civilians seem to be getting too anxious about our set-up. We should have moved out a couple of days ago, but attack seems imminent so I guess we have orders to remain until it begins”[xv]. Major Ralph Ingersoll of the 12th US Army Group Special Plans branch visited to pass on a warning. The enemy was regrouping and becoming more aggressive. Civilians Luxembourgers reported seeing Germans in nearby woods. Shots were heard. Telephone wires laid by the Signal Company were found cut.[xvi]

Finally, on Saturday, September 22nd, the 83rd Infantry was ready to move in to hold the line for real. To preserve the deception, the sonic trucks carefully played the sounds of tanks moving away as the fake Sixth Armored division pulled out in the night. Soon they were in Luxembourg City. The operation was judged a success. Patton’s line had held, and after eight days along the front, the Ghost Army slipped away.[ix]

The story of the Ghost Army was kept secret for more than fifty years after World War II. Since their exploits were kept under wraps, accounts of actions they took part in often erase their role. Take, for example, a brief history of the 3rd Cavalry published at the end of the war. It described those weeks along the Moselle this way.

“During this time, the handful of men (760) in this squadron [43rd Cavalry Squadron] kicked up such a fuss with the help of supporting artillery, that the German G-2’s reported everything from an armored combat command to several divisions in the 23 mile front zone.”[xx]

But the official after-action report of the 3rd Cav gave credit where credit was due: "The establishment of a "simulated armored division" during this period by 23 Hq Special Troops . . . added to the bewilderment of the enemy as to our strength. All indications pointed to the fact that he thought we were in great strength in this sector, as he continued to increase his forces along the river to counter-attack our "armored thrust." [xx]Another great review for the Ghost Army.

​

[i] Account of Operation Bettembourg by Clifford Simenonson, Clifford G. Simenson Papers, US Army Military History Center, Carlisle PA

[ii] Report of Operation Bettembourg, 15-22 September 1944, dated October 14, by Lt. Colonel James Snee

[iii] Polk, James; World War II Letters and Notes of Colonel James H. Polk, p 87

[iv] Fox Fred; Fred’s World, unpublished manuscript in the possession of his son, Donald Fox. Also, Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, National Archives

[v] Combat Command “A” Operation Bettembourg, Repot by Lt. Col. E.W. Scroeder, National Archives

[vi] The evidene that CCA was in the woods north of Abweiler is overhwhelming. Most important are the multiple map overlays found in the files of the 23rd at the National Archives. Once laid over the appropriate US Army maps, they clearly show the locations for the troops in CCA, CCR and the (fake) 6th Armored Division HQ. Also, according to an unpublished history of the 406th Engineers, a copy of which is in the Ghost Army Legacy Project archive, they bivouaced “one mile north of Abweiler.”

[vii] Combat Command “A” Operation Bettembourg, Report by Lt. Col. E.W. Scroeder, National Archives

[viii] “Report of Sonic Operation Bettembourg; 15-22 September by Robert Hiller, dated October 15, 1944, National Archives

[ix] Author interview with Richard Syracuse, 2006

[x] “Signal Report on Operation Bettembourg”, dated 12 October 1944, National Archives

[xi] “Summaryof Special Effects for Operation Bettembourg” by Major David Bridges, National Archives

[xii] Account of Operation Bettembourg by Clifford Simenonson, CLiford G. Simenson Papers, US Army Military History Center, Carlisle PA

[xiii] Journal of activiies during Operation bettembourg, found in National Archives, author unknown (first page is missing.) Also, LUXEMBURG BEFREIUNG UND ARDENNEN OFFENSIVE 1944-1945" from E.T.MELCHERS . 1981 Sankt-Paulus-Druckerei..(Editions du Centre, J.-P.Krippler-Müller, 1959.)

[xiv] Author interview with Bob Conrad

[xv] Diary of Bob Tomkins, entry dated September 21, 1944. A copy of the diary is in the Ghost Army Legacay Project Archives

[xvi] Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops

[xvii] Blumenson, Martin, editor, The Patton Papers 1940-1945 p 552.

[xviii] Polk, James; World War II Letters and Notes of Colonel James H. Polk, p 90

[xix] “Report of Sonic Operation Bettembourg; 15-22 September by Robert Hiller, dated October 15, 1944, National Archives, Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, National Archives

[xx] “Brief history of the 43rd Cavalry Rcn Sq (Metz)” taken from the Bowie Blade, Camp Bowie TX, 31st August 1945 issue.