Task Force “Z”

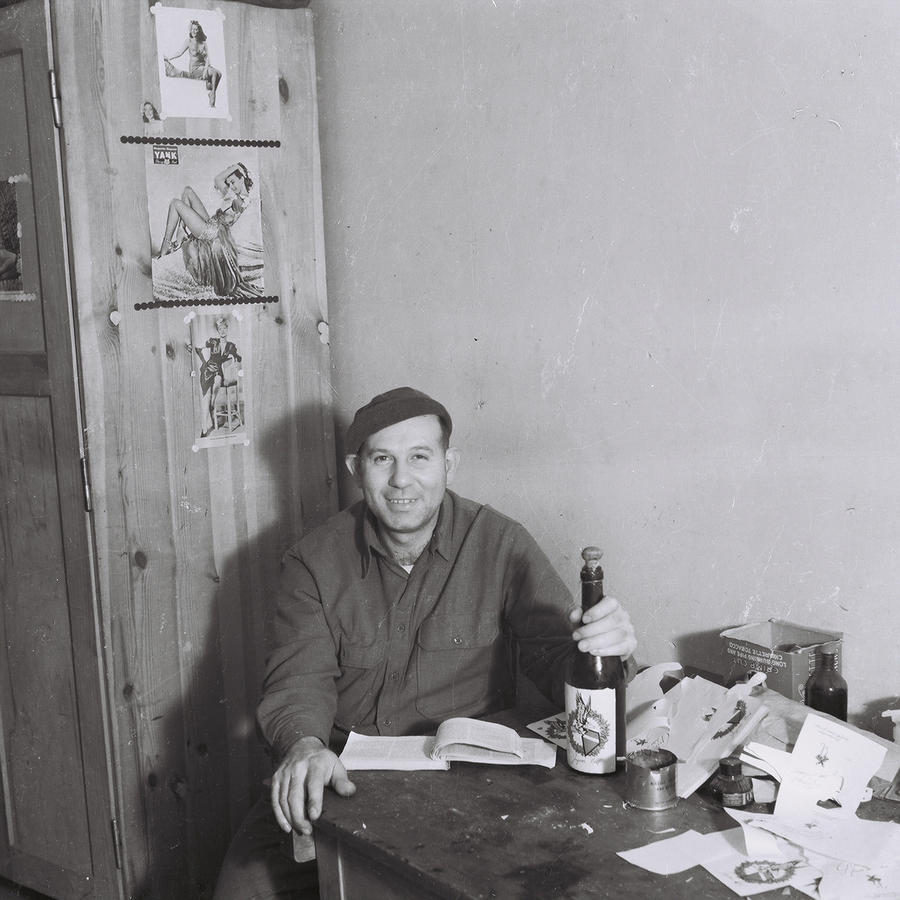

From the collection of Irving Mayer.

For a time the men of the first platoon thought they would have to bear the cruel burden of guarding the Lesneven bivouac, collecting eggs and cavorting with the local maidens. But no, 23rd staff had show VIII Corps. another position where deception could be used.

Lt. Col. Simenson was selected to command this third operation. With the remaining 149 men and 10 officers still in the area, he formed task force “Z.”

The general plan for T. F. “Z” was to simulate the 69th Tank Battalion of the 6th Armored Division. To do this, Co. “A” 709th Tk. Bn. Was to be expanded by the use of three rubber dummy tank companies plus radio, sonic and special effects. The simulated Bn. would supposedly be in support of the 29th Infantry Regiment.

At 1500 24 August, “Z” pulled into its operational sector, a site located on a slope overlooking the village of Milizac, one mile to the southeast. This location was selected because it could be observed from the ground by the planeless Germans.

Once in the area, bumper markings and shoulder patches were put on and the radio began sending its deception. As soon as the conversion to the 6th Armored was effected, the men began digging in. An 88 landing one hundred yards down the slope intensified the digging.

The first real tank of Co. A arrived at 1800 hours and after being marked with the 6th Armored devices began tracking the fields selected for the dummy positions. By nine o’clock, the whole of Co. A had arrived and the tanks were placed in the most conspicuous spots for the benefit of passersby on the road.

406 men threw a guard around the entire sector so no unauthorized person could enter. The erection of the dummies began at 2230 hours.

Those men who did not go on guard continued digging. The excavating was no sooner finished than it began to rain. And, then, the word came that the second and third squads of the first platoon were going out to guard the Heater while it played a tune for the Germans.

At 2200 hours the two squads moved out of the bivouac, passed through the village of Milizac and continued on until the German lines were but 500 yards away. Here, under the direction of Capt. Rebh and Lt. Daly, S/Sgt. Ernest Brodbeck and Sgt. Harold Anderson set up a security system around the sector picked for the sonic tracks.

It was originally planned to have the sonic effect between 2245 and 2345 hours. However, while awaiting the arrival of the Heater, Capt. Rebh moseyed up nearer the front. There he learned of an impending infantry battalion attack at 2300 hours. The attack was for the purpose of clearing the line of departure for the assault that was set for the next day August 23 at 1300 hours.

Realizing that a major disturbance on the sector, fifteen minutes prior to the attack, would alert the Germans and might prove disastrous to the infantry, Capt. Rebh returned to the sonic area and informed Col. Simenson of his findings. The Colonel immediately postponed the time for the sonic program until 1:10 in the morning.

Now the men of the second and third squads, before going out on the job, had been informed that the “show” would be over by midnight. The night was inky black, the skies poured down rain. To the rear, artillery roared, to the front burp guns chattered, everyone was wet cold and jumpy and when midnight passed without the “Heater” even showing up, the men cursed up and down.

At last the sonic half tracks lumbered down the road, moved into position and played in a tank battalion, from 0110 to 0140. It was nearly three o’clock when the two squads returned to their rain soaked bivouac. The night had been a bitch.

The next day came bright and clear and Colonel Simenson and the commander of the tankers went into the town of Milizac. There they climbed the church steeple and gazed toward T. F. “Z.” A whole tank battalion met their eyes and the tank officer commented that it sure looked like the real thing. It was the battalion that the Germans had heard moving into position at 0110 hours that morning.

The fine weather gave Uncle Sam’s air force an opportunity to have a go at Brest. The planes put on a first class show for this was the softening up before “H” hour. Men of Task Force “Z” saw the fighter bombers come over in waves and drop their missiles. Then the fighters came in to strafe the ground positions. Time after time, the planes seemed goners as they dived into hails of tracers but they always seem to pull out.

Not to be outdone, the artillery opened up and sent its power crashing into the German front lines. At 1300 hours the infantry attacked and the artillery lifted its fire, concentrating on the enemy’s heavy guns.

All day and all that night, the attack continued. At night the bombardment had a quality of terrifying beauty. The flashes of the artillery mingled with glowing lights of hundreds of flares and the sudden brilliance of bursting bombs. All this accompanied by a thunderous obligato. Guards coming off shift stayed up to watch the scene. The gods of battle were performing for the master race.

During the night the dummies were taken down. Dawn brought S/Sgt. Brodeck around to all the posts with the news that the problem was over and the guards were to come in at 0600 hours. When the guards came in, patches and bumper markings were removed and the task force resumed its role of a nonentity.

All phases of operation Brest were finished. The objective of bluffing the defenders into surrendering the port was a failure. However, information gathered after the fall of the city showed that the enemy believed there was a large armored force confronting his positions at Brest. The enemy was deceived into thinking that it was there.

Capt. Rebh and other students of the military arts in 23rd believed that a situation such as Brest was not the proper place to employ the deception unit. Brest was a well defended fixed position, the defenders had no problem of frustrating maneuvers confronting them. A deception organization should be employed to influence the enemy’s maneuvering of his troops.

In his critique, the Captain also brought out that many did not realize the potential of deception. He cited the battle order that sent five light tanks to their destruction when they moved against the front that task force “X” had been influencing.

The collection of hand grenades carried on task force “Z”’s mission caused considerable excitement when one exploded. Somehow a taped grenade fell off a cartridge belt and the jar when it hit the floor of the third squad set it off. Pvt. Irving Mayer noted the smoking explosive and quickly heaved it into the next field where it exploded.

The noise and the whistling shrapnel caused everyone to hit their holes. “The Germans were zeroing in on the area” was the thought that ran through the men’s minds.

For a while it looked as though Mayer was going to be court martialled for his quick work. But, later, an investigation by the Captain cleared him and left him a little dazed about the whole affair.

All went well after the grenade incident and by the same evening Task Force “Z” had rejoined the rest of 23rd at Lesneven, the base assembly area.

That night some of the men enjoyed the spoils of a mission that had taken place during the problem. At that time 1st/Sgt. Jules Toth and Sgt. Bill Duckworth accompanied Capt. Rebh on a trip to a forward O. P. On the way the party encountered a soldier who claimed he was looking for a sniper. But, the hunter carried in his left hand a bottle of joy juice. Noting the direction the soldier came from, it was but a few minutes when the 406 men were looking into the cellar of the Milizac rectory.

Shades of Cognac Hill! --- there before them was at least a thousand cases of assorted liquors. A mental note was made of the cache and the trip to the O. P. resumed.

Later while Capt. Rebh was peeing from the O. P., the two Sergeants decided that it was sheer folly to let that cellar goods lay there idle. So with Punchy Feldman at the wheel, they hurried back to the rectory. And none too soon, there was the old mean F. F. I. men loading the stuff onto trucks. The trio managed to load up all the peep would hold before going back to the O. P.

The first night back at Lesneven, with the rules relaxed, the booty was distributed in a pass the bottle fashion among the men. Somehow the supply ran out too fast or someone wanted more than his share. At any rate, a person, or persons, raided Sgt. Duckworth’s personal share and removed two bottles of cognac. The following morning, August 27th, Task Force “A” started on its way back to headquarters. The weather was clear and the beautiful Brittany scenery appeared at its best as the convoy rode toward Rennes.

That afternoon the trucks pulled into a bivouac a few miles outside of Rennes. 406 vehicles had no sooner come to a halt, than the men were ordered to take all their gear out of the trucks and lay everything out for a showdown inspection.

Capt. Rebh was more than displeased by the disappearance of Duckworth’s two bottles of eau-de-vie. Needless to say, there was no trace of the plunder, not even the corks. However, a few men located articles in their duffle bag that they had given up for lost months ago, so all was not in vain.

In the evening, the personnel of T. F. “A” was told that there would be unofficial passes for all but the area guards. Rennes was “off limits” so visiting the city was up to each individual’s own judgement.

Most of the soldiers found places between the city and the camp to spend their free time. However, a few employed their knowledge of infiltration tactics and entered the […]. One trio thumbed a ride in a civilian vehicle and rode right past the M. P. post in grand style. All who visited the city had a grand time.

Next day, the task force resumed its journey and reached Torcé-en-Charnie, the new location of 23rd Hq. where they rejoined the combat third platoon.

While the company proper was fulfilling its mission at Brest the rear echelon, consisting of Lt. Aliopoulos and the third platoon, was ordered to a more maneuverable position. At 0800 on August 23 they swung south and west, arriving at 1400 at a point 2 ½ miles south of Torcé-en-Charnie, having travelled a distance of 120 miles by motor convoy. From here they could expeditiously reinforce our forward elements to the west in the Brittany peninsula, or form a spearhead of deception in a move toward Paris, with the ultimate objective of eliminating the Wehrmacht in France.

The five days of outstanding holding action of this group added to the fine job the main body was performing with the task force. Of particular note was the adequate protection given 23rd Hq. against the ever present danger of roving bands of German stragglers. In this connection the action of one combat patrol deserves special mention.

At about 1800 on 25 August, Major Bridges called 23rd Hq. asking for a patrol of 8 men and one NCO to report immediately. About a dozen volunteered, and were all sent, with Sgt. Fitzgerald in charge. Arriving at headquarters they found Col. Reeder, Maj. Bridges, Lt. Reeder, and two French civilians waiting for them in a jeep. The party then sped to a woods outside a nearby chateau, where the patrol immediate dispersed, locked, loaded, crawled through the woods in extended formation, and finally surrounded the building, paying particular attention to the exits. The men were instructed to allow no one to leave the area.

With these precautions taken, the Colonel drove to the entrance of the chateau with his jeep. He asked permission of the owners, who were sitting there, to search the premises. When his request was refused, the colonel went to see the mayor.

Meanwhile, one of the volunteers, Pfc. Kehlman, questioned the two civilians who had asked for the patrol, and gathered that the owners of the chateau were sympathetic to the Nazis, and were reported to be in the pay of the Reich. The two Frenchmen charged that these collaborators were harboring two Germans, one of them a woman, and thus would not allow a search. They further charged that there were tunnels leading from the chateau to the woods nearby. Through these, an estimated thirty-two Nazis entered the chateau each night to get food, and would return via the same passageways to their sylvan hideouts. The owners, when questioned, denied any knowledge of this. They admitted they had two visitors, but would not way who they were.

According to the two French patriots, the mayor of the town was also of questionable loyalty. Thus it was no surprise when the Colonel returned with word that the mayor had likewise refused him permission to search the house. The Colonel then ordered the patrol to withdraw, but not before asking Pfc. Kehlman what had been said. Kehlman repeated the above story, and asked why it was necessary to have permission to enter the grounds, under such extenuating circumstances. The Colonel sagely explained that special troops must be diplomatic at all times. Chagrined, but nevertheless aware of the seriousness of their position in the war, the twelve diplomats slung their rifles, and walked back to the vehicles.

The Frenchmen, it was reported, were not so diplomatic. They informed the Maquis, who diplomatically bashed in the door, and corralled all the culprits, including the reported thirty-two stragglers.

Other patrols of a different nature met with greater success during this period. Farm fresh eggs, butter, roast chicken, rabbit, and similar contraband was among the war booty gleaned from these foraging sorties. One soldier in his zeal, went on a patrol to Neuvelette, forgetting to take his shirt with him. On his return he also discovered that he had forgotten Article 6 of the MCM [Manual for Courts-Martial], which stipulates the necessity of having official leave before an absence. Some time later a court-martial impressed it further on his mind and pocket to the tune of ninety days and $30.

On August 28 the remainder of the company reported from duty with the task force. The usual exchange of combat experiences took place, and soon the other platoons had deployed themselves about the countryside in an effort to relieve the third platoon of their patrolling activities.

On the evening of August 30 the company was alerted. Capt. Rebh called a company meeting and explained that the unit was scheduled to move into the neighborhood of Dijon, then held by the Nazis, to simulate a move by the U. S. Third Army to effect a junction with the U. S. Seventh Army, then moving swiftly north along the Rhône valley.

With a “this is it” lump of excitement in their throats, the company, having loaded nets and equipment after dark the night before, was rolling out of Torcé-en-Charnie at 0630 the morning of August 31. After a day of hard riding past such famous sights as the Cathedral at Chartres, the organization arrived one mile southeast of Mauny at 2020. The wistful looks at the signposts indicated the proximity of Paris were to no avail. The unit was adamant in its pursuit of the trail so recently blazed by General Patton’s blitz.

The stopover at Mauny proved to be more than a march halt. It developed that successful use of a deceptive force depended to a good measure on being in a position to move swiftly to any front. Between the time the plan had originated in higher headquarters, and the time it took for the outfit to get to Mauny, the situation had materially changed. Furthermore, like General Patton and other combat echelons, the unit began to feel the lengthening of supply lines where it hurt most, i. e. in the shortage of gasoline.

Stymied by the rear echelon’s failure to deliver the necessary fuel, the men through their own initiative and reconnaissance, found other sources of liquid energy. Lt. Kelker acted as S-2 on this operation. He espied other units loading up with the precious fluid while on a mission of a different nature. On his return, he filed a report with Lt. Robinson, who was in command during the Captain’s absence. The lieutenant did not feel he could authorize the use of gasoline for the purpose in mind, but happily, an arrangement was made with one Lt. Hunter of another organization, who happened to have two vehicles scheduled to make the run, and which otherwise would have had to return empty handed.

The reservoir of the liquid, consisting of 520 cases (6240 bottles), was located in a large warehouse just outside of nearby Seines. The building was chock full of Wehrmacht equipment, by far the largest part of which was the aforementioned liquid known variously as eau-de-vie (water of life), brandy, or cognac. A French soldier on guard at the entrance, accepted as bone fide credentials, the international “laissez-passer” of the Americans, called in French, “le pass Chesterfield.” S/Sgt. Tuttle and Pfcs Kerstein and Kehlman, members of the detail, carefully sampled the material for booby traps. Finding the chemical contents to their utmost satisfaction, the booty was loaded and subsequently brought to the bivouac area, where the “load” was distributed throughout the organization.

Added to this individual acquisition was the official cognac breakdown, by the Third Army, of captured enemy liquor stores. One of the primary missions of the 406th while at Mauny was the guarding, distribution, and use of these stores. For this reason the period has come to be referred to as “Operation Cognac Hill.” As usual, the mission was successfully completed, with the action of the combat engineers the same credit to the outfit as always. Capt. Rebh’s policy, of maintaining conduct become a soldier regardless of the circumstances, was adhered to strictly.

The bivouac near Mauny lasted for a week, during which time, in addition to the consumption of liquid supplies and “fresh” issued eggs, the immensely popular film, “Ghostbreakers” with Olsen and Johnson, was shown four days running. This, the longest holdover in the Blarney Theatre history, was not entirely by demand. The film had been borrowed from an Air Force unit back near Coutances. The shortage of gasoline made it impossible to return it, and equally impossible to get a new one. Many considerate movie-goers thought it would be doing other organizations a favor to bury it then and there, as the best solution to the problem.

At 1300 on September 7 the outfit, throwing deception to the winds, began a frontal attack on Paris. St. Germain, rumored variously as ten minutes to ten miles from the city proper, was to be the first objective. The march party passed the famous resort town of Fontainebleau, then swung northeast past the wreckage of several large airfields including Le Bourget (of Lindbergh fame) where reconstruction work was already in progress. The Eiffel tower was almost constantly in view as the convoy made nearly a complete circle around the city, passing through Versailles, the beautiful town of torn treaties. At last, the Chateau Vielle was sighted, and the narrow streets of the picturesque Parisian suburb of St. Germain-en-Laye was entered. At 1800, after traveling a distance of 130 miles, the occupation of La Maison d’Education de la Legion d’Honneur (Les Loges), three kilmetres out of the town, was effected.

St. Germain, birthplace of Claud Debussy, was a favorite retreat of the French court. Chateau Vielle, built by St. Louis, was the home of Francois 1er, the Renaissance leader. It was rebuilt by Napoleon III and today serves as a museum. Chateau Neuf, built by Henry IV, is now mostly in ruins.

This, then, was the town that Blarney took by storm. Jump off point was from Les Loges, which before the war had been a ritzy girls’ school. The men ruthlessly tore down the pictures of Hitler, which the Germans had left on the walls in their hasty departure. Reconnaissance parties in search of mattresses and other conveniences, ran across German medical supplies and literature. Unlike the culture-destroying Nazis, our men studiously acquired dictionaries, atlases, grammars, and other books from the almost inexhaustible supply in the chapel, rather than permit them to be destroyed in the event of a German counter thrust.

The following night the forward elements of the pass patrols, after a rapid street by street reconnaissance, established contact with the first main objective of the campaign. Here once again the value of fighting on friendly soil was emphasized. No matter from what quarter of town the various task forces entered, the French freely gave information which enabled the entire organization so inclined, to pay their respects at Club 26. Said establishment, a school for teaching “French,” naturally appealed to the majority of the unit personnel, who were studious and hungry for knowledge of France, - her ways and customs.

The “auditorium” of the school had a congenial attitude. A five piece band provided atmosphere for the music lovers. Cognac and other beverages helped stimulate the academic spirit, while the schoolmarms, in brassieres and panties, helped erect social goodwill. For a payment of fifty francs to the Dean, one could go upstairs to the comfortable classrooms for a personalized lesson by one of the pulchritudinous schoolmarms. Another fifty francs was paid here for the service, as well as ten francs to a towel girl, so the slate could be wiped clean for the next lesson.

The students who received these lessons returned downstairs with the highest praise for the instructions. The knowledge gained, however, seemed to be quite ephemeral, for in another half hour the student usually felt the urge for a refresher course.

One evening, one of the teachers was in the midst of a lecture on the dance and anatomy downstairs, when one of the soldiers attempted to combine the upstairs lectures with the downstairs’, amid the cheers of the student body. The Dean, however, frowned upon the irregular proceedings. When her cries of “Agent de Police” failed to bring about the desired decorum, she appealed to the band master to play the Star Spangled Banner. This appeared to be a successful maneuver, for it brought the entire aggregation to attention. Scarcely had the last note been sounded, however, when the combined lesson in dancing, anatomy, and experimental physics was once more prosecuted with renewed vigor. The appreciative student body greatly benefited by these new approaches to pedagogic methods.

The stay at Les Loges included other ways of enjoying the fruits due a combat weary group of liberators. Pass convoys were authorized to nearby Versailles, where the time was spent mostly in sightseeing, souvenir hunting, and paying exorbitant prices for food and what little drink was still available. Some were lucky enough to hear Dinah Shore and her entourage entertain for the boys behind the Palace.

On Sunday, September 10, word spread that passes to Paris were going to be authorized. At that time, the City of Light was still off limits to any but those with official business. However, it was difficult for the MP’s to decide who was on official business, and who on monkey business. A list was submitted to Captain Rebh of all those who wanted to go there. Names were then picked at random, and the lucky non-coms piled on a truck to spend an afternoon in the world famous capital. They were met there by some of the less fortunate privates who had to resort to AWOL hitch hiking tactics.

The Paris they entered was a city where an American soldier was still a novelty. The Champs-Élysées was packed with Sunday throngs attired in the colorful, imaginative, world-renowned Parisian way. The bicycle traffic was as dangerous as the military, especially when one’s eyes were irresistibly drawn to the shapely, stockingless legs that were undeniably chic, even when vigorously engaged in pedaling. The cigarette, and ration, and trade flourished under the Eiffel tower. Prices during those days were as high as 300 francs a pack, or sixty dollars a carton. However, in return, the restaurants and bars were charging unheard-of prices for what little they had. Perfume, on the other hand, was dirt cheap, and not at all hard to get. The officers were kept busy for weeks afterwards, censoring packages of Chanel, Guerlain, Molyneux, Lucien LeLong, and many of the other first rate brands.

It was generally agreed by all who visited the city that the beauty and forwardness of the Parisian “jeunes filles” was in no way overrated. The advances of designing women were not easy to repulse, but the stalwarts of the 406th were no soft touches. Where others succumbed paying 500 francs, the combat wise men of Blarney White held out for 450 or less, once again bringing credit to their worthy unit.

Some of those who saw Paris ran greater risks than apprehension by the MP’s. Unlike most of the other units, the 406th had a nightly bedcheck to forestall any mass departure for the capital. Most of those who tempted Lady Luck were able to get back in time. A favorite method was to persuade some none-too-sure-of-his-way GI driver who wanted to get to Versailles, that he need seek no further for directions. After a pleasant half hour’s ride, the grateful Blarney man would hop off at St. Germain and port to the sign clearly indicating the road to Versailles – 13 kilometers away. The actions of the dumbfounded driver were usually just short of apoplexy, for Versailles was only 12 kilometers from Paris by the direct route.